Published April 2010 Vol. 14 Issue 4

by William Hillyard

photo by Preston Drake-Hillyard

In this THIRD installation of his series on Wonder Valley, William Hillyard explores two men’s lives as they intersect in the arid isolation of the Mojave Desert.

Night in Wonder Valley is vast and limitless; out there, no lights distract the stars. Looking up, you see infinity. The heavens shroud the earth with the dust of the Milky Way, the ancient pulse of countless stars in that eternity of darkness. Out there, the sky appears torn from the earth along the jagged silhouette of the mountains—those mountains, along with the dilapidated homestead shacks and the empty sand and scrub of the Wonder Valley floor, sink into a featureless black void. Late, in the calm of the deep night, you can find yourself out there in an ear-crackling silence, in a darkness without form. All you are is your breath rasping in your chest, your heart lub-dubbing in your ears. Life, the entirety of your existence, collapses to a mere spark, the briefest blush of daylight in an endless night.

Out there, with the cosmic canopy hanging heavy above, Tom Whitefeather sits in an old rocking chair staring out the open door of Raub McCartney’s rock-walled cabin into the night. Raub’s dusty, half-drunk jug of wine sits at his feet. The rock-walled cabin sits anchored to the flank of an island, a scab of weathered boulders, part of that inky nighttime silhouette rising from the barren basin of the valley. Whitefeather will make his bed on Raub’s antique settee behind the old rocking chair, wrapped in a blanket against the cold darkness of the rock-walled room. He never goes into Raub’s room; it sits just the way they left it, with the boxes overturned, the bed covered with clothes and photos. They left it with the closet door sprung open, the contents spilling out onto the floor. They left it with the box fan on the floor and the bullet hole in the wall.

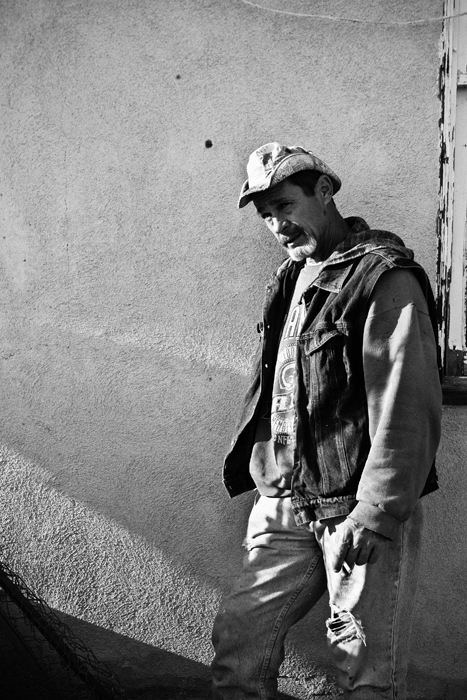

Tom Whitefeather stands outside Raub Mc Cartney’s rock walled cabin in the mojave desert.

Tom Whitefeather stands outside Raub Mc Cartney’s rock walled cabin in the mojave desert.

It seems there may be something of a feminist (feminine?) revolution bubbling under the surface of Denver’s artistic communities. In last month’s VOICE, I wrote about the no holds barred Titwrench music festival, a local festival of progressive female music and culture that is run and operated by a group of strong, independent women. The festival is an all-inclusive look into contemporary feminist culture and the sounds that go along with it.

It seems there may be something of a feminist (feminine?) revolution bubbling under the surface of Denver’s artistic communities. In last month’s VOICE, I wrote about the no holds barred Titwrench music festival, a local festival of progressive female music and culture that is run and operated by a group of strong, independent women. The festival is an all-inclusive look into contemporary feminist culture and the sounds that go along with it.