The People vs. Thomas Ritchie

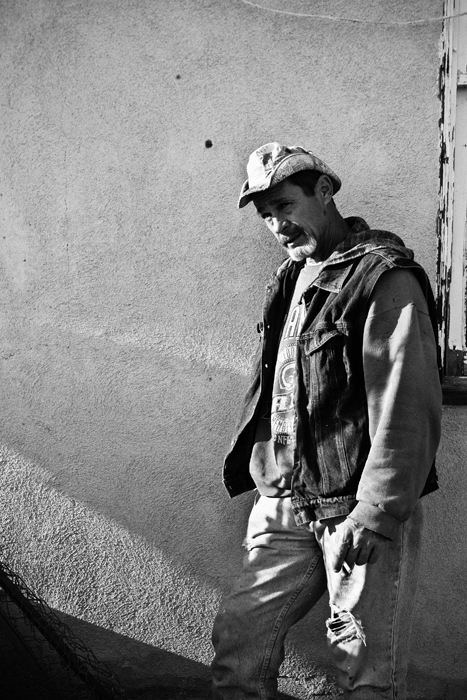

Tom Whitefeather wakes at two in the morning on the days he has to go to court. He scarfs a quick breakfast, then bundled against the cold and the Wonder Valley night, he heads out from the old rock-walled cabin where he lives, threading a path through the high desert greasewood scrub. A dim headlamp bobs a blue-white orb ahead of his bike as he rides in the pre-dawn stillness following his own tracks, cutting across abandoned homestead parcels, through the sandy washes and brittle bush thickets until he reaches the washboard dirt track of Godwin Road. Down Godwin he peddles to the lonely asphalt of the paved road, then turns his back to the rising sun for the last twelve miles to the bus stop in town. He’ll make this trek a dozen times—the arraignment, the fact-finding hearings, the readiness hearings, postponements, postponements, postponements. On the mornings he goes to court, he gives himself plenty of time, arriving at the bus stop with time enough to scrounge discarded butts and roll a smoke. He gets there early and he waits. To miss his court appearance would mean another felony, and more time in jail.

Tom Whitefeather wakes at two in the morning on the days he has to go to court. He scarfs a quick breakfast, then bundled against the cold and the Wonder Valley night, he heads out from the old rock-walled cabin where he lives, threading a path through the high desert greasewood scrub. A dim headlamp bobs a blue-white orb ahead of his bike as he rides in the pre-dawn stillness following his own tracks, cutting across abandoned homestead parcels, through the sandy washes and brittle bush thickets until he reaches the washboard dirt track of Godwin Road. Down Godwin he peddles to the lonely asphalt of the paved road, then turns his back to the rising sun for the last twelve miles to the bus stop in town. He’ll make this trek a dozen times—the arraignment, the fact-finding hearings, the readiness hearings, postponements, postponements, postponements. On the mornings he goes to court, he gives himself plenty of time, arriving at the bus stop with time enough to scrounge discarded butts and roll a smoke. He gets there early and he waits. To miss his court appearance would mean another felony, and more time in jail.

Tom Whitefeather had already spent the five days in jail. Sheriff’s deputies had handcuffed him at the Cat Ranch, pushed him into the back of the patrol car, arrested him in violation of Section 597, paragraph B of the penal code of the State of California. Too much pussy, Whitefeather’d tell you. Cruelty to animals is what the People of the State of California say, failing to provide his kitties with proper food and drink and shelter and protection from the weather. A felony.

Over the next week, a county animal control officer trapped 53 cats at the Cat Ranch—the old Wonder Valley homestead where Whitefeather had lived—took them to county shelters, and destroyed them.

Tom Whitefeather would tell you all this himself, if you met him. He’d tell you that after Raub McCartney died, he had moved himself into Raub’s old rock-walled cabin. He’s not squatting there; Raub’s cousin said it was OK. When the cousin came out from back East to take care of Raub’s final affairs, she told Tom she thought it’d probably be best if someone were around to look after the place—you know how things are out here, as soon as people find out a place is vacant, they’ll break in, steal everything—the doors, the windows, burn the furniture for firewood, trash the place. She’d hate to think of what would happen to the old rock-walled cabin if it were left abandoned.

Whitefeather would tell you that even after he moved away from the Cat Ranch he has taken good care of his kitties, made the trip every day pedaling over the rocky crag that separates Raub’s from that isolated parcel of the Cat Ranch. His kitties were healthy, he’d tell you, ask anybody. He’d tell you how he worked for people just for his kitties, asking them to pay him in cat food rather than cash, how every day he cooked for the kitties: ten pounds of chicken with two pounds of dried beans, adding potatoes and rice and sometimes canned vegetables all bought with his meager food stamps and boiled together for eight hours. Every day. He’d tell you how he rode the dusty Wonder Valley roads dragging the red wagon filled with food, the ten pounds of chicken boiled with beans, how he returned again, every day, with ten gallons of water, did the best he could until that one day, when he arrived to find two patrol cars pulled up against the scrap wood walls of the Cat Ranch compound, two deputies inside.

They had an arrest warrant for someone Whitefeather had never heard of at a house nowhere around here. Were these his cats? His kitties? How many? Eighty?? This place looks like the county dump! You can’t tell me this place was maintained! The deputy, the one with the raptor head and the deep set hawk eyes, did all the talking. Sure, the place had gotten away from him what with having to cook every day for eight hours and haul the food and water behind his bike the mile over the rocky pass from Raub’s place. But he did his best.

Sheriff’s deputies had been at the Cat Ranch for 45 minutes before Whitefeather arrived that morning, photographing the cats, documenting the conditions: the overwhelming stench of cat urine and feces; the smell of decomposition. No food, no water for the cats. They’d photographed countless cats amid filthy squalor, videotaped the dead kitten lying on the kitchen floor, another cat eating it. They documented the bones of dead cats strewn about the place, gnawed-on and half eaten, paws and fur still attached. And then there was the whole cat, rotten to a pool of putrescence curled up in the fridge—you could still see its little ears and eyes and nose.

You probably wouldn’t even notice the Cat Ranch even if you drove the dry, dusty roads that mark off the square of scrub desert where it sits. You’d probably have a hard time seeing it even if someone—like Ned Bray, maybe—pointed it out, telling you about that Indian, Whitefeather, he had like a million cats, man, and he was arrested—yeah, he spent like five days in jail. You should go talk to him, man. You want a story, go talk to Whitefeather. He lives right over there. But he’d be pointing to a void, no right over there over there, just an accumulation of lumber and pallets and strewn about rubbish in the middle of a quarter section of empty desert.

Tom Whitefeather might take you to the Cat Ranch, if you met him, take you up the forgotten driveway marked by white-striped tires, around the rubble of boards and junk, past piles of cat shit, three feet high and ten feet in diameter, to a palisade of up-ended plywood, sun-burnt and sand-blasted. Fortifications, Whitefeather’d tell you, keeping the marauding coyotes away from his kitties.

Inside the worn gate of the Cat Ranch, the acrid reek of cat piss hits you like a cold-cock. It invades into your nose, soils your tongue; it pricks at your eyes, dousing you in stench, washing through your hair, you wear it in your clothes. The cabin, its walls and floor, and the litter and trash and the cats and the gnawed-on, half-eaten bones are the color of dust. Dry, dust-colored twists of cat shit hang weightless from the edge of plant pots, fill the basin of the sink, the rumpled covers of the bed. A litter box overflows, more shit than sand. Gray garbage bags bulge with garbage.

Tom Whitefeather’d tell you that he did his best to keep the place clean. He lived there for three and a half years, and the place wasn’t like this then—ask anybody. He loved his kitties; all of them had names—well, except for the last few litters. There were just too many, it’d all just gotten away from him. He’d prayed to God to help him. If you talked to Whitefeather, he’d show you the raked-up heaps of feces ready to be hauled outside and dumped in the mounds outside of the plywood parapet, except that his wheelbarrow has a flat; he’s patched it over and over. He’d show you the bones the cops saw strewn about the property. See? he’d say, goat bones. Bones from the goat he slaughtered to feed the kitties. He’d tell you he saw that little kitten the cops found dead the night before when he came to feed the kitties and bring them their water. He’d seen the kitten; it ate well, but later seemed sick, like it was on its way out. He’d picked the kitten up, it felt limp to his touch. He put the kitten with its mama, he’d say, and was going to return the next day with a box to carry it back to Raub’s place to give to Mama Kitty, the mother of them all, to nurse back to health. And that’s what he was doing when he showed up at the Cat Ranch that morning in August when the two patrol cars were there and the two deputies inside.

Of course, Tom Whitefeather doesn’t own the Cat Ranch. It belongs to that German artist who bought it as a place to produce his art. To the German artist, Wonder Valley, this new artist Mecca, was a place between worlds. You drive out from Los Angeles, past the last of civilization, the trappings of American excess so glaring, into a land of drifting tumbleweeds, nights dark as death, a people from another century living with no water or electricity.

When the German artist bought the place, Whitefeather came with it. The German artist didn’t stay long, and you know how things are out here, as soon as people find out a place is vacant, they’ll steal everything, trash the place. The German artist felt sorry for Whitefeather, too. He could live there he told him, live in that old broken down motor home parked in front of his new Wonder Valley cabin, look after the place. Whitefeather had two kittens back then: a boy and a girl. That was the summer of 2006. The German artist never returned.

Over a beer, Tom Whitefeather might tell you he came to Wonder Valley way back when to lay low after his undercover work—busting a drug kingpin down in the city with the DEA, his former employer. Wonder Valley is a good place to hide out, to fly under the radar. He’s not here because he wants to be. If you had the kind of past he had, he’d tell you, you’d understand. You shouldn’t even ask about his time in the Corps, his time as a Marine Corps sniper, black ops. You can’t just leave that life behind, you know, you can’t just walk away—they won’t let you. He was in ’Nam, he’d tell you, De Nang, doing wet jobs deep up country first, then elsewhere around the world. He can’t tell you where they sent him, of course, during those eight years, but suffice it to say that the jungles of South America are as dank and nasty as anything in South East Asia. Everyone in Wonder Valley knows not to talk to him about his time in the Corps; they just give him that knowing nod for his sacrifices, let him help himself to their beer, their cigarettes, slip him a couple of bucks for his kitties.

Now Tom Whitefeather is stuck in Wonder Valley. First stuck cooking for the kitties eight hours a day, and now stuck with The People vs. Thomas Ritchie, this animal cruelty felony hanging over his head. Whitefeather is Tom’s Indian name, he’d tell you, that is how everyone in Wonder Valley knows him. He’d tell you his mother gave him that name when he was just a child. He doesn’t remember much about her, she wasn’t around much. His childhood is a flash of images, a slideshow with no chronology, no narration, out of order snapshots of a kid in San Diego. He remembers getting hauled into the police station with his brothers, his earliest childhood memory. Police picked him up while eating out of trash cans in a back alley; his two older brothers, aged four and five, fended off the stray dogs with sticks so their little brother could eat. Tom was two.

He and his brothers were taken from their drunken, drug-addled mother various times and returned to her again. Ultimately, authorities removed them to an orphanage. He remembers he got a toy tool set for Christmas that year, wooden hammer and screwdrivers, the only thing he’d ever had that was truly his. Time and again, Tom’s brothers escaped the orphanage, leaving little Tom alone until they were apprehended and returned to the home. Eventually, the boys were settled in the rural San Diego County home of foster parents, Tom taking his toy tools with him. Finally, authorities shipped them off to relatives in farm town Iowa.

If you’d asked Tom’s brothers, they’d tell you Tom had a fondness for cats even back then. In fact, he felt closer to animals than he did people. While his brothers teased, tormented, and tortured the farm cats, Tom fought to protect them.

The rest of his life, his adult life, is an uncertain tale—half-truths and borrowed narratives clumsily mixed with true events. It would take you a lot of time to parse together what is real about Tom, what is Tom and what is Whitefeather. He never joined the service, for instance, though his brothers did. They shipped off to Vietnam: one became a sniper in the Marines; the other went into the Navy. Tom, still in high school, knocked around the Iowa town. The Jehovah’s Witness missionaries in town had a really cute daughter, Tom would tell you. When they knocked, the missionaries and the daughter, Tom let them in. They prayed. When they asked to come back, Tom looked at the daughter and said sure. Together they read the Bible; for Tom, the world began to make sense, his life gained meaning. He joined the church, immersing himself in it, moving to Brooklyn, to the dormitories at the Jehovah’s Witness headquarters, and worked as warehouseman shipping their flyers.

He held good jobs at times through the nineties, banging nails when construction was booming, working as an exterminator, sometimes living in a proper apartment, bringing home a proper paycheck.

He was 42 when he got the first of his string of DUIs; he lost his driver’s license. He was in the desert by then, at the beginning of a slow spiral. Then a second and a third DUI, another marriage in a drugged-out and drunken fog, then finally convicted and sentenced to a bullet--one year behind bars.

He hasn’t really had a home since. Out of jail, he worked as the yard dog for a contractor, living in a trailer on site, then, losing that job, lived in an old broken down van. A fellow Jehovah’s Witness offered him some charity, towed his camper up to the Mojave, gave him a place to park it. He met others, worked odd jobs, towed his camper around Wonder Valley until those kids gave him those two kittens and he moved into that ramshackle shack bought by the German artist.

If you were hanging out with Tom Whitefeather on a certain morning and you were driving past the Cat Ranch, you’d have seen a car parked there, a rental car. And sleeping in the back of the car, hugging himself against the January chill, you’d have found the German artist. Tom would knock on the window and the German artist would wake with a start and look at Tom and you in a jet-lagged haze. The German artist, having arrived after dark, wouldn’t have seen the condition of his property yet, not seen the notice tacked to the gate warning against admittance under penalty of a misdemeanor, calling the Cat Ranch “Unsafe for Human Habitation.” He’d have received the notices of violation from the county, though—the requirements for the abatement of the cat urine and feces, the list of infractions including structural defects and building code non-conformities in the decades-old homestead cabin, like wrong size windows and too small rooms, as well as the bills for the fines incurred for non-compliance. And you’d have found him a little testy.

“I let you stay here, gave you money. You were supposed to clean the place up, get rid of the trash!” he’d have snapped at Tom, spinning in circles, his arms held wide in a just-look-at-all-this gesture. The sun would already have begun to pink the German artist’s balding head, redden his nose. He’d have been wearing shorts and sandals in spite of the January chill.

“You only gave me $800 dollars!” would be Tom’s retort, incredulous. “Only $800 in three years!” Tom’s creased face would be accustomed to the sun; his grey goatee on his clenched, set jaw jutting out of the shade of his rolled hat.

“I gave you $1000 dollars!” the German artist would say, backing up, stepping to avoid a pile of dusty turds.

“It was only $800, remember? You took $200 back because you were going to L.A. and needed the cash…”

“Oh, well, I gave you $800! I paid you! I paid you and you did nothing! You were supposed to take care of the place, you call this taking care of the place?”

“I…I moved that pile of trash there,” Tom would say, pointing to a heap of rubble. “That stuff used to be IN the cabin! You should have seen this place before,” he’d say to you, trying to draw you into the argument. “What did he expect for only $800 in three years?”

“I paid you $800! I paid you! Most people have to pay rent to stay in a house! Look at this place!” Again, the German artist would spin in circles, his mouth agape, stammering speechless. A dust-colored cat would slink past haltingly.

After his arrest, the court had mandated that Tom have no contact with animals as a condition of his release. But Animal Control only picked up 53 cats from the Cat Ranch, leaving the rest. What was Tom supposed to do, let them starve? He fed those kitties, pedaling to the Cat Ranch from the rock-walled cabin under cover of darkness, a bag of cat food strapped to the front basket of his bike. When the German artist showed up at the property a dozen or so kitties remained there.

If you had been there that morning, you’d have heard the frustration in the German artist’s voice. “You have to get the rest of these cats out of here or I’ll call animal control,” he’d have said with resolve.

That spark would have detonated Tom, “You do that and I’ll sue you!” he’d have screamed, clomping after the German artist, who would have begun tramping over the trash and rubbish, a matted tomcat staring down at him from the corrugated metal roof.

“You have three days to get these cats out of here.”

“I need a week.”

“OK, you have a week,” would have been the German artist’s resigned reply.

Hindsight is 20/20, Tom Whitefeather’d tell you. He’d not have taken that female kitten for one thing, if he’d known how this would all turn out. That was his mistake—he’d never had a male and female before. He might have tried to get them fixed, too. He doesn’t believe in that, though, it’s against the will of God, his kitties are God’s creatures, not his. That’s why he never gave any away. He just couldn’t trust anyone to take care of them, not the way he could, what with the coyotes, and you know the way people are out here.

Sure, he’ll tell the court that he couldn’t afford the spaying and neutering costs: $125—each. And he’d tell the court how he’d tried to get county vouchers, but the vouchers never arrived. He’d tell the court how he just couldn’t find the kitties proper homes.

Six months after his arrest, after a dozen trips threading through the high desert scrub in the middle of the night, a jury of Tom’s peers would deliberate for eight hours about the charges in the case of The People vs. Thomas Ritchie. They’d have sat through days of testimony, pictures of countless cats amid filthy squalor, descriptions of the eye-burning stench, ninety-some-odd exhibits, debates about cat bones and goat bones, and a video of an emaciated cat eating the head of a dead kitten. They’d hear that Tom was overwhelmed, that he couldn’t care for all the cats, that he had let them breed rampantly with no thought as to the consequences. They’d hear how he worked not for money, but cat food, how he bought it by the 16-pound sack, a dozen at a time. They wouldn’t hear that Tom cared for those cats like he hadn’t cared for anything in the world before—not since the little toy tool set—that they gave him purpose. Yes, he was overwhelmed, yes, they’d hear him say to the deputies in the played-back recording from the back of the patrol car, “I prayed to God just this morning to help me, to lift this burden, and when I arrived, you were here.”

The jury would find Thomas Ritchie not guilty of felony cruelty to animals. If you asked them, they would say it’s a matter of degrees. Sure, he was guilty of something, but not a felony. They’d say what a waste of time and money, here when the state is going broke.

The jury would have seen Tom well up with tears as they announced their verdict. He’d go home that afternoon acquitted of all charges. Maybe you’d have given him a ride, through the dots of desert towns, past the Marine base and the national park back to Wonder Valley, driving down the last lonely strip of paved road with the setting sun at your back. Congratulations, you might say, congratulations beating that rap. And you’d drop him off there, at his home, at Raub McCartney’s rock-walled cabin, and you might notice his old broken-down motor home, towed over from the Cat Ranch, sitting in the drive. And you’d notice that it is already filled with cats.