Published October 2009 Vol. 13 Issue 9

by William Hillyard

Jack McConaha answered my knock in a white t-shirt. “Come on in; have a seat,” he said. “Say hello to the kids.”

His ‘kids,’ two toy poodles, yipped at me from the side of the king-size bed that practically fills the windowless living room of his sprawling Wonder Valley cabin. The dogs’ bed and food and water bowls sat in the rumpled covers. The whoosh of the swamp coolers covered the room with a blanket of white noise, reducing the TV at the foot of the bed to a murmur.

Jack disappeared to finish dressing. “Must have picked up a nail,” he shouted from deep within the warren of the house. “I checked the air in my tires this morning and one was a little low.” It seemed he was continuing a conversation that had begun before I arrived. “Don’t matter,” he went on, “it’s just down a couple of pounds.”

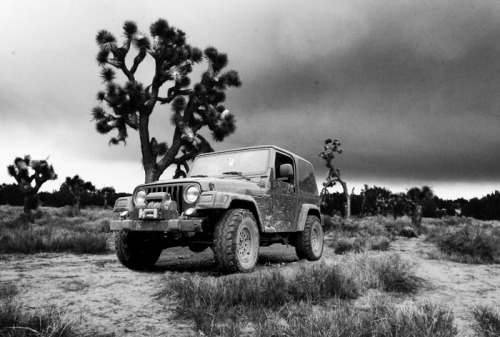

Chatting constantly, he told me he doesn’t like the Firestone tires that came on his new patrol Jeep. He’s going to replace them, he said; get BF Goodriches—they self-seal if you get a puncture.

Jack reentered the room dressed for his desert patrol; summer weight camouflaged fatigues—Marine Corp issue—draped from his short, stout frame, a 40-caliber Smith and Wesson on his hip. The tin badge on his breast designated him “Captain of Security.”

Jack’s hand, resting on the grip of his pistol, showed the faint scars of the welding accident that earned him his lifetime of disability checks, the money he has lived on for his nearly 40 years in Wonder Valley.

He came to this hardscrabble desert enclave when it was still largely peopled by pioneering “jackrabbit homesteaders” brought to this area by the Small Tract Homestead Act of 1938, which carved Wonder Valley into five acre parcels free for the taking. All you had to do was to “prove up” your parcel: clear the land, build a cabin. When Jack arrived here in the early 1970s, some four thousand cabins flecked this remote patch of desert. These days only a thousand or so still stand—and half of those sit vacant. The remaining few house the snowbirds and retirees, artists and writers, drifters and squatters that live out here along Wonder Valley’s nearly 400 miles of washboard roads.

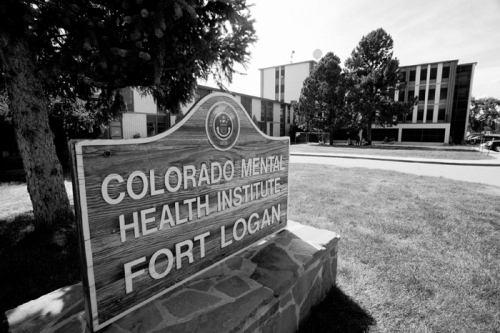

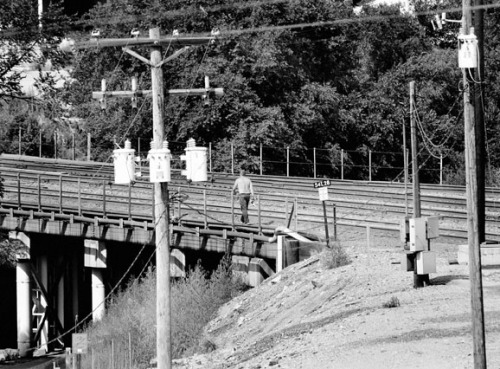

Jack volunteered as a fireman when he first arrived; even did a stint as chief of the area’s small all-volunteer brigade. Now he’s the one-man security force patrolling the valley’s lonely roads. Some people come to these abandoned cabins and empty desert from “down below,” from L.A. and that mess down there by the coast, to cook up drugs or dump a dead body or just wander out into the saltbush scrub and blow their own brains out. Jack told me about the Wonder Valley man he came upon, standing in the sandy lane, bashing his wife’s head with a rock. He told me about the meth labs he busted, the all night stakeouts, the search and rescues. He told me about the people he’s helped, how they tell him how much they appreciate what he does. He talked of the commendations he’d been awarded, citations, newspaper clippings, the luminaries he met in the line of duty as the self-appointed guardian of this remote corner of the Mojave Desert.