'You Got This:’ Inside the Moment Shrek Broke the Fourth Wall

Photos and Story by Giles Clasen

‘You Got This:’ Inside the Moment Shrek Broke the Fourth Wall

Photos and Story by Giles Clasen

Kelly McAllister was in sixth grade when his teacher interrupted class with news that didn’t fit the shape of an ordinary school day.

“I remember Mrs. Kelman came in and said, ‘Something awful happened. The mayor of San Francisco and Harvey Milk have been killed,’” McAllister said.

The assassinations felt close. McAllister grew up about 50 miles outside San Francisco, but at the time, he did not know who Milk was or that he was the first openly gay elected official in California. He didn’t know about Milk’s role in urging the LGBTQ+ community to come out and claim visibility. None of that mattered to him yet.

What stayed with McAllister was the violence itself.

“I was like, ‘Jesus Christ. What is going on here?’” he said. “I cared that they were murdered. I thought that was just wrong, and I remember it hit me hard, even then.”

That idea of right and wrong is what McAllister says resurfaced decades later, standing inside a community theater in Parker. This time, a request to remove Pride flags from “Shrek the Musical” at the Parker Arts, Culture and Events Center (PACE) became a test of how he understood and applied his own moral code.

McAllister runs Sasquatch Productions with August Stoten and has directed theater in Parker for years, including “Shrek the Musical." “Shrek” is a family-friendly story about an ogre who wants to be left alone in his swamp,but instead finds connection and love with a princess, who is hiding a secret of her own.

Early in the show, the villain Lord Farquaad banishes fairytale creatures he deems “freaks” from the kingdom and sends them to Shrek’s swamp. Later, those same characters reclaim the insult in a celebratory ensemble number called “Freak Flag.”

McAllister said the song’s lyrics clearly point to themes of LGBTQ+ identity and acceptance. In “Freak Flag,” Gingy, the living gingerbread man, sings, “We weren’t so freakin’ strange. They made us feel that way. But it’s they who need to change.”

Later, Humpty Dumpty adds, “It’s not a choice you make. It’s just how you were hatched.”

“I think [LGBTQ+ identity] is what the song is about,” McAllister said. “It’s about acceptance for who you are and acceptance by the larger community. It’s very loving and accepting in a joyous way.”

It felt natural to McAllister to choreograph rainbow Pride flags waving at the end of the song.

"I thought maybe [the Pride flag] could help queer kids see that they’re not alone. And on top of that, it can help straight kids understand that maybe you should be cool and not be a jerk to the kid who’s different than you,” he said.

McAllister is not alone in his interpretation of the song. Since its Broadway debut in 2008, “Shrek the Musical” has frequently been read as an LGBTQ+ affirming story, particularly for its embrace of difference and its refusal to frame belonging as something that must be earned.

The Reuters review of the 2008 Broadway production ran with the headline, "Shrek's a family musical with gay-Pride element." In the Reuters coverage reviewer Frank Scheck pointed specifically to "Freak Flag" as carrying a "gay-Pride subtext."

According to a Town of Parker statement, they received "a variety of complaints" when McAllister turned the subtext visible with the waving of the Pride flag during the song. Parker's Communication Manager, Andy Anderson, pointed all questions to the Town's published statement.

"As a Town-owned performing arts venue funded in part by taxpayer dollars, the Town has a responsibility to remain neutral," the statement said. "The Town did let the producers know about the concerns brought to the attention of the Town but did not demand or require that any part of the show be removed or modified."

Denver7 reported that one sponsor of the show, Lutheran High School, emailed parents a statement. The school said they had a strong partnership with the Town of Parker and PACE, but would pull their sponsorship for “Shrek the Musical” for the remainder of its run.

"This year, we chose to continue our sponsorship of the family musical with [the PACE] presentation of the show, “Shrek.” After the first weekend of shows, we were made aware of content in the production that did not align with our mission and values," the email said.

The school did not respond to email requests for comment.

McAllister said that neither the Town of Parker nor PACE ever required the flag be removed from the production, but he was asked to reconsider using the flag. Contractually, he had the freedom to choose whether to use the flag and other creative decisions.

McAllister took the suggestion to the cast, who voted to keep the rainbow flag in the song and production.

"I thought maybe [the Pride flag] could help queer kids see that they’re not alone. And on top of that, it can help straight kids understand that maybe you should be cool and not be a jerk to the kid who’s different than you,” Kelly McAllister said.

Breaking the Fourth Wall

In theater, stopping a show mid-performance is rare. The word actors use in moments of danger or urgency is "hold," Bekah- Lynn Broas said.

That is the word Broas chose during the January 23 performance.

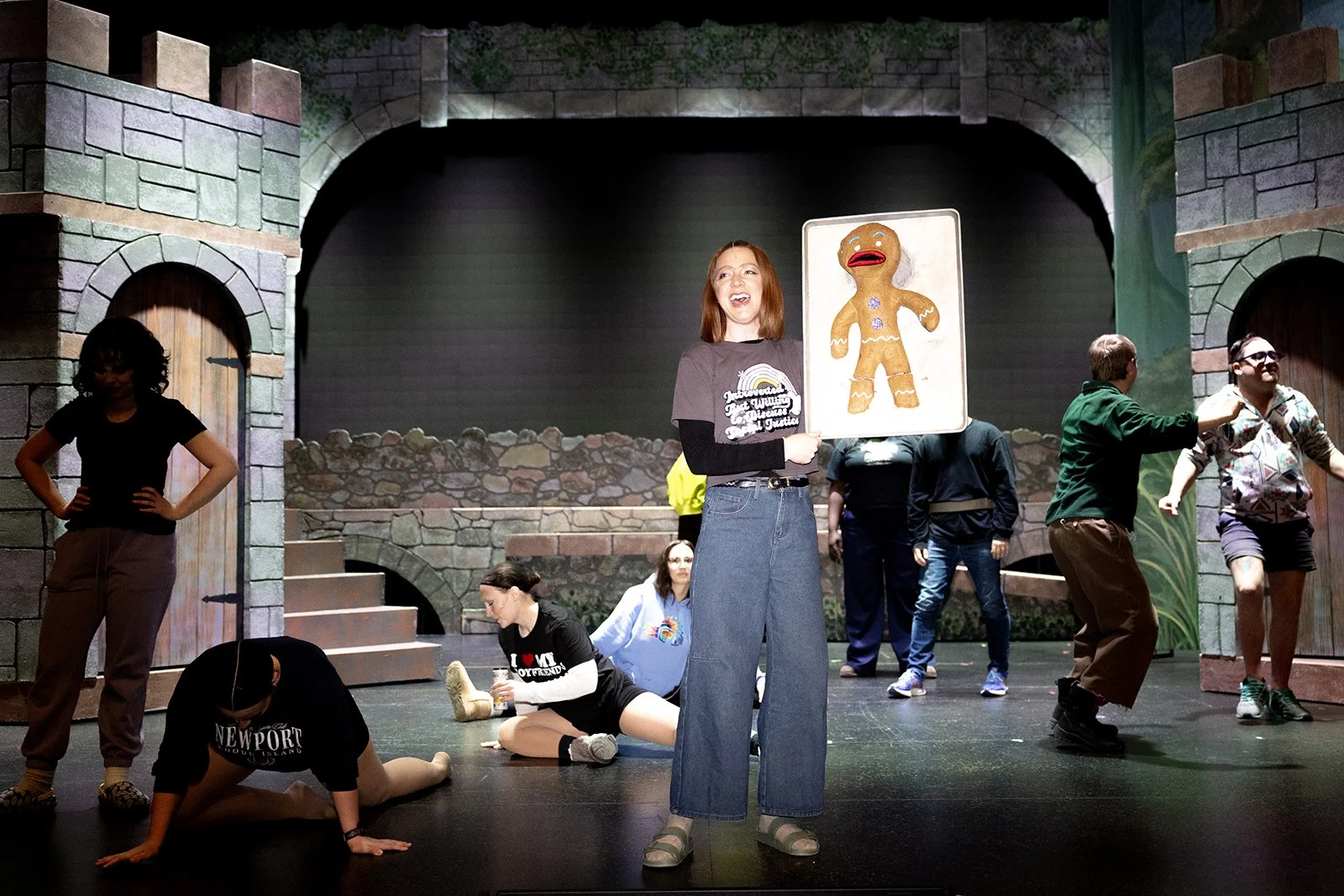

Broas plays several roles in “Shrek the Musical,” including the Sugar Plum Fairy and Gingy the Gingerbread Man. Her character opens the song "Freak Flag."

Just before the ensemble cast performed “Freak Flag," Broas called “hold” and broke the fourth wall to explain to the audience why the cast had decided to continue flying Pride flags. She said the moment came from a collective understanding backstage that the song’s message, about those who are banished, labeled as “freaks,” and told they do not belong, directly mirrors the lived experiences of the queer community.

Broas, who describes herself as a proud ally, spoke on behalf of the cast when she told the audience that the show is about inclusion and acceptance of all people, including the LGBTQ+ community.

"The message that … what you are witnessing tonight is about inclusion, it is about community, and about loving your neighbor, no matter what they look like, or how they identify," Broas said to the audience on January 23, captured in a video uploaded to YouTube by McAllister.

“She gave the speech. The song started. She started to cry. So, I just yelled out from the theater, ‘You got this. You got this,’ because I wanted them to know that I was there and that I had their back and everything was going be okay,” McAllister said.

The fourth wall exists to preserve comfort and illusion, just as social norms often expect marginalized communities to remain visible only on approved terms. By stopping the show, Broas made explicit what is often left unspoken. Inclusion frequently requires interruption.

In that moment, breaking the fourth wall mirrored a broader reality. Progress rarely happens quietly, and making room in shared civic spaces often means challenging the rules designed to keep certain people unseen and voiceless.

Broas said she was deeply unsettled when the cast was told to reconsider using the Pride flags.

“My stomach dropped,” she said. “I felt pretty saddened and upset.”

For Broas, the issue went beyond staging. Broas said the note hit the cast as something more than a response to complaints and criticism.

“It was not a suggestion,” she said. “It was a direction.”

To Broas, the stakes were clear. Keep the flags, and the show could lose funding, putting the show itself “in limbo.”

Bekah-Lynn Roas practices the song “Freak Flag” before a performance. "The message that … what you are witnessing tonight is about inclusion, it is about community, and about loving your neighbor, no matter what they look like, or how they identify," Broas said to the audience on January 23, captured in a video uploaded to YouTube by McAllister.

“Shrek” is a highly professional performance with expensive sets, technical effects, actors, and live musicians. McAllister said the performance cost well north of $100,000 to produce. Losing a sponsor had the potential to be devastating.

“This could have been our last show,” Broas said. "We didn't know, but we decided it was important to take a stand."

Broas said neutrality was never an option. Removing or avoiding the Pride flag, she said, would itself have been a political statement.

“Silence is complicity,” she said.

If identities are censored or erased from public representation, then neutrality is nothing more than silent participation in the censorship, Broas said. Attempting to be “neutral” participates in harm by allowing discrimination to go unchallenged. For Broas, the choice was not between politics and art, but between inclusion and exclusion.

“Censorship of identities is something to take very seriously," she said. "It harms people, it discriminates."

After she spoke directly to the audience, Broas said she felt physically shaken, overwhelmed by the weight of what she had just done. Nothing had prepared her for such a brazen act outside of theatrical norms. Still, she remains clear about her choice.

“I would do it again,” she said. “I just tried to do the right thing.”

Cooper Kaminsky, who plays Shrek in the production, said the request to remove the flag made them feel unsafe and disappointed as a queer individual.

"Every day presents new attempts at erasing queer people from media, from art, from history, from the world," Kaminsky said. "Sometimes just existing, waving a flag, and saying 'Hey, I’m here. I'm okay, you are too,' can be enough to change another queer individual’s life for the better."

Kaminsky said continuing to be themselves onstage and seeing that authenticity embraced by audiences has been deeply validating and empowering. They believe that theater can have a lasting impact even after a single performance, even in a show like “Shrek.”

During a recent performance, the loudest applause during the show came when the Pride flags came out during "Freak Flag." Audience members at the sold-out performance made their support clear when they stood and cheered. Inclusion and acceptance resonate.

"Every day presents new attempts at erasing queer people from media, from art, from history, from the world," Cooper Kaminsky said. "Sometimes just existing, waving a flag, and saying 'Hey, I’m here. I'm okay, you are too,' can be enough to change another queer individual’s life for the better."

The Case for Empathy in Public Spaces

Mike Waid occupies a rare intersection in the story unfolding around “Shrek the Musical” at the PACE Center. On stage, he plays the Captain of the Guard. Off stage, he helped build the institution itself.

Waid is a former Parker city councilmember and mayor who voted to build the PACE Center not long after the 2008 recession. Even then, bringing arts and culture to Douglas County, a conservative stronghold, was deeply contested.

Later, as mayor, he performed on its stage for the first time in West Side Story.

His dual work, bringing the PACE center to Parker and performing on its stage, gives him what he described as “some historical perspective on the facility itself and what it actually means to the creation of art.”

From the beginning, the PACE center represented a philosophical divide.

“There’s some folks who just don’t think governments should be in the arts and culture business,” Waid said. “There’s those who think that arts and culture represent an intrinsic value to a community. I’m one of those that believes that way.”

The value of the PACE center was also economic, bringing people into town where “they eat at restaurants, they fill up with gas, they buy stuff at stores, and provide sales tax revenue,” he said.

The facility, he said, has done exactly what we hoped it would, becoming “a catalyst for not only community arts and creative development, but also for economic development and impact in our community.”

The PACE Center was always intended to offer the community multiple entry points to the arts.

“When we built PACE, we insisted it could not be a single-use facility. It could not be just a theater. It could not be just a venue,” Waid said. “If we were going to invest the money of our taxpayers, we needed it to be a true community hub for everyone in the community. And that’s what we created.”

Waid identifies as a Republican, a detail that complicates easy narratives around the controversy sparked by Pride flags.

"In all honesty, I personally did not see the flag as an issue at all,” he said. “It’s a creative expression. The creative license of having the Pride flags, which were out for all of maybe three minutes in a three-hour performance, is just a way of including everyone.”

Waid said the story's theme of inclusion is unambiguous from beginning to end and hits hard for any member of the audience, child or adult. He pointed out that the message isn't limited to those who identify as LGBTQ+ but to all community members.

“It’s such a beautiful story, and it’s such a beautiful play that hits on so many levels," Waid said.

For Waid, Shrek’s message of inclusion is what makes life interesting and worth living.

“Life would be so freaking boring if everyone was a big, fat bearded guy like me,” he said. “What makes us all so incredible is our uniqueness. It’s beautiful that there’s so many versions and varieties of humans out there. We just need to make space and welcome one another.”

That belief extends beyond the stage. Empathy, he said, doesn’t require agreement, but it does require making space for each other, trying to understand each other, and accepting each other.

“It doesn’t mean I have to destroy them because they like something I don’t. We just need to accept each other and invite everyone to the table,” he said.

“When we built PACE, we insisted it could not be a single-use facility. It could not be just a theater. It could not be just a venue. If we were going to invest the money of our taxpayers, we needed it to be a true community hub for everyone in the community. And that’s what we created,” former Mayor and Councilmember and performer, Mike Waid said.

Waid argues for relationship over rigid adherence to ideology.

“It takes as much material and effort to build a bridge as it does to build a wall,” he said. “But the difference is when you build a bridge, you can meet the other person, and you can talk face to face

He framed empathy as a matter of effort in caring for one another over dogma.

"When you use all of that time and energy and resources and materials to build a wall, you never have the luxury of seeing that person face-to-face or eye-to-eye," Waid said. "All you're doing is banging up against that wall.”

Waid said it was a no-brainer to keep the show staged as originally directed by McAllister. He hopes that the conflict around the Pride flag doesn't prevent PACE and the Town of Parker from working with Sasquatch Productions and McAllister in the future.

"Sasquatch does amazing, professional performances. They're a great group of dedicated people,” Waid said. “I hope, beyond any complaints in the short-term, that Sasquatch is still invited to participate with the PACE Center.”

The Pride flag on the props table for “Shrek the Musical” at the PACE Center.

Why Shrek Lands Differently Right Now

“Shrek the Musical” explores who is welcome in the community, who is not, and who gets to decide. The show begins with an ogre being told, explicitly and repeatedly, that the world is “not for you.”

When Shrek ventures out of isolation, a woman screams at the sight of him. He is judged before he speaks, feared before he acts, and treated as something that must be removed rather than understood. He self-deports himself from the play's kingdom of Duloc to a swamp, where he is safe from judgment, but lives in isolation.

For Shrek, the idea of miserable isolation is preferable to open judgment. His life turns around when the character Donkey sees past his warts and finds Shrek's intrinsic value. Their budding friendship leads to adventure, acceptance, and family.

Duloc, Farquaad’s immaculate kingdom, is introduced as a place of sameness and control.

The sorting, purifying, and banishing from Duloc by the villain Lord Farquaad runs through the production as he plots to become king through lies and deceit. Fairy-tale characters are rounded up by Farquaad's militaristic guards, and the character Pinocchio jokes that Farquaad's agents are sending the "freaks" away, dumped into Shrek’s swamp after being declared undesirable.

Lord Farquaad tells the freaks, “You and the rest of that fairy-tale trash are ruining my kingdom.” The villain later sings, “Once upon a time, this place was infested. Freaks on every corner, I had them all arrested.”

McAllister said the musical resonates in today's political climate. Those who fail inspection are removed. Order is enforced through spectacle, humiliation, and violence, including a gingerbread man tortured for information, all played for laughs, but never without consequence.

To Jacob Frye, who plays the Big Bad Wolf and other characters in the musical, the dispute over a Pride flag and the erasure of queer identity from public spaces was never abstract.

“Seeing [the Pride flag] in a major theater production would have helped me realize when I was younger that there are more queer people than I thought there were, that I wasn't alone,” Jacob Frye said.

Frye identifies as queer and said that he grew up learning that he was not accepted within what society labels as “normal.” This was difficult for him, but he found acceptance in theater, a space for outsiders and the LGBTQ+ community. Frye was in high school when he first met McAllister, who was teaching at Stage Door Theater about 10 years ago.

The Pride flag, he said, represents far more than identity. It signals safety, shared understanding, and the presence of people who recognize one another’s lived experiences. He sees acceptance not as a default condition, but as something that must often be defended and reaffirmed.

Frye described growing up surrounded by images of heterosexual, cisgender life presented as universal, not maliciously, but relentlessly. It was a message that he feels communicates to LGBTQ+ youth that they are different, outside the norm, and to a degree unwelcome.

“Seeing [the Pride flag] in a major theater production would have helped me realize when I was younger that there are more queer people than I thought there were, that I wasn't alone,” Frye said. “It would have sparked an investigation into what that meant and helped me identify parts of myself earlier.”

That is why representation cannot be treated as a matter of politeness or tolerance alone. Queer visibility, he said, carries emotional and psychological weight because it counters years of being told, implicitly or explicitly, to be quieter, smaller, or grateful for conditional inclusion.

“We didn’t want to be quiet,” Frye said. “It was more important to be loud in the face of that bigotry than to cede to their demands.”

To Broas, one of the final lines in “Freak Flag” carries the message the cast fought to keep visible.

Pinocchio’s line, “I’m wood. I’m good. Get used to it,” lands as a declaration, one that echoes decades of Pride protests and public insistence on being seen.

For Broas, the line does not demand agreement, only recognition. “Inclusion of all people does not mean exclusion of you if you’re different,” she said.

That insistence, she added, is not a modern insertion but something already embedded in the script.

“Harvey Milk said, not just Milk but many in the queer community in the 70s, said, ‘We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it.’ It is in the script. It is obvious to me,” she said.