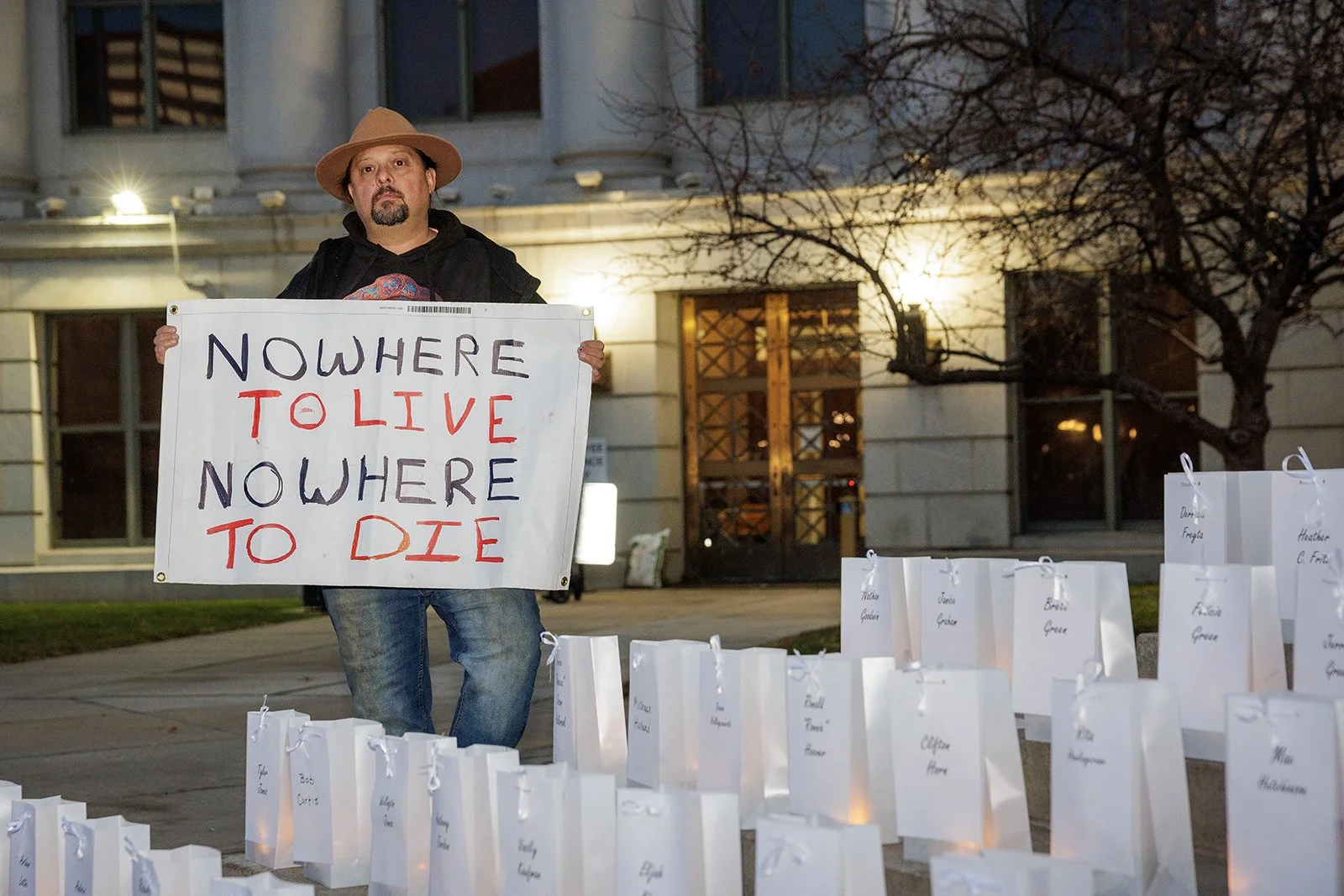

274 Lives Remembered at Denver’s We Will Remember Homeless Vigil

Story and Photos by Giles Clasen

Tammy Charbonneau stood quietly as she listened to the names read, her hands clutching a candle and a program. She had come to the 2025 We Will Remember: Homeless Persons’ Memorial Vigil to honor her son, Thomas, who died on Mother’s Day.

“I miss him every day,” Charbonneau said. “The pain is never going to go away. It becomes a part of you. It's something you learn to live with.”

Charbonneau said her son’s adult life was shaped by a traumatic brain injury he suffered in a car accident ten years earlier. The injury affected his mental health and made stability difficult to maintain.

He turned to drugs to cope, then was unable to escape addiction.

“He chose to do a walkabout because he didn't wanna drag me down,” Tammy said.

Thomas’s death came suddenly, after he ingested drugs contaminated with fentanyl, a loss she described as both devastating and impossible to prepare for. She said no parent should have to experience the loss of a child, and yet, she knows she is far from alone.

“The pain is never going to go away. It becomes a part of you. It's something you learn to live with, but it never goes away,” Charbonneau said

Each year, the We Will Remember Homeless Vigil gathers families, service providers, advocates, and community members to honor people who died while experiencing homelessness in the Denver metro area. This year, 274 individuals’ names were recognized.

The vigil, organized by the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, is held annually on the longest night of the year, a time chosen deliberately to reflect the danger of living without a home.

The names of those who died were read into the dark one by one, each followed by the crowd responding, “We will remember.”

“This might be the only remembrance ceremony some of these people ever have,” said Cathy Alderman, the coalition’s chief communications and public policy officer. “We come together because people who die while experiencing homelessness are too often invisible, in life and in death.”

Alderman said there is no excuse for individuals dying while experiencing homelessness.

“We as a community just need to do more,” Alderman said. “We cannot continue to let this many people die on the streets of Denver, not when we have an abundance of housing available, even though it's not affordable for most folks. We need to do something about making sure that it is affordable, and we need safer places for people to be, so that they're not passing away while experiencing homelessness.”

As the ceremony continued, the street in front of the City and County Building carried another form of remembrance.

Laid across Bannock Street were hundreds of handmade quilts and blankets, displayed as part of a first-time partnership with the Memorial Blanket Project.

The quilts, stitched by volunteers across the country, formed a large-scale public display meant to represent both the scale of loss and the fragility of life without shelter. After the vigil, the blankets would be distributed to people experiencing homelessness through shelters and outreach teams.

Pat LaMarche, one of the founders of the Memorial Blanket Project, said the quilts are meant to make homelessness visible in a way words often fail to accomplish.

LaMarche said the project grew out of years of attending candlelight vigils that, while meaningful, often felt abstract. She wanted people to confront the reality of homelessness in a way that demanded attention. She wanted something that could not be ignored or quickly walked past.

“A blanket is simple,” she said. “But when you think about how much it matters when you don’t have one, it changes how you see the problem.”

She described the installation as both a protest and an invitation, a challenge to the idea that people experiencing homelessness are somehow different or deserving of their circumstances.

“If you’re sitting with a blanket that you’re creating for 100 hours, eventually, don’t you have to wonder how the person who’s going to get it ended up there?” LaMarche said.

LaMarche said many of the quilts are made by people who are experiencing homelessness.

“One woman was in a shelter, and she was trying to make us 17 blankets, and she ended up giving us six because 11 of them went to other people in the shelter,” LaMarche said. “That’s what people miss. Even when people have almost nothing, they are still caring for one another.”

Alderman said the visual presence of the quilts brought a different kind of attention to the vigil.

“They create a moment where people stop and ask what’s happening,” she said. “And once they know, they understand why this matters.”

Alderman said fewer deaths were identified this year compared with recent counts, something she attributes in part to more people being brought indoors. But she emphasized that the number of lives lost remains unacceptable.

“It’s still far too many,” she said. “We know what works. Housing with supportive services saves lives, and we need to keep investing in those solutions.”

For Chinalyn Cole, who works with Recovery Works in Jefferson County, the vigil is both familiar and deeply personal. She said she returns every year, knowing she may hear names she recognizes.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Cole said. “These are people you’ve served, people you’ve known, sometimes people you’ve cared deeply about. And you can’t help but think that if they hadn’t been in the situation they were in, their lives could have been much longer.”

Cole said the quilt installation added a new layer to the vigil and felt it was important for her to volunteer in laying out the display.

“The memorial is really beautiful and a symbol of the care and commitment and love,” Cole said. “Hours go into making these quilts, by a complete stranger that doesn't know any of these individuals, they’re pouring their love into this. It's really beautiful and a contrast to what I think individuals experiencing homelessness usually experience when they're, you know, oftentimes not even acknowledged.”

She said the vigil often brings complicated emotions for people who work in the homelessness response system.

“There’s guilt,” Cole said. “There’s always that feeling that maybe you could have done more, especially now when some supports are being reduced. But being here with other people who care reminds you that you’re not alone.”

Cole pushed back against the idea that homelessness is a personal failure.

“People don’t choose this,” she said. “It’s circumstances. Things snowball quickly: an accident, an illness, mental health, a job loss. Most people are much closer to homelessness than they realize.”

As names continued to be read, some attendees shouted out the names of friends, partners, or other people they knew who lived in shelters or encampments and were not on the official list.

Charbonneau remained nearby, standing quietly as the ceremony came to an end. She said she appreciated that the vigil offered her son some recognition.

“He’s free now,” Charbonneau said. “He’s not the one in pain. We’re the ones left behind.”