Life on the Edge of Homelessness: Elevated Denver exhibit uses photography to challenge stereotypes

Story by Giles Clasen

Photos by Brown Public

Elevated Denver has invited the public to see homelessness through a new lens. Its latest project, “Life on the Edge of Homelessness: A Storytelling Experience,” showcases photographs taken by people living on the brink of losing housing or already without stable shelter.

The September exhibit, which opened at Cameron Church on Sept. 18, featured photographs, personal narratives, and mirrored prompts for visitors, all designed to push audiences to reflect on their own experiences and assumptions.

“The intention of the project was to honor our roots at Elevated Denver in storytelling, and to sort of cultivate compassion among all of our community. We wanted to allow people to step into the space where they can see what life is like for people who have shared and different experiences and to really understand that there’s a lot more that binds us than separates us,” said Johnna Flood, cofounder of Elevated Denver.

Over two weeks, artists used the camera in their phones to document daily challenges and moments of meaning. Flood and her team then worked with each participant to pair images with narratives written in the artists’ own words.

One of the artists who participated in the project is a Denver VOICE vendor who asked to be identified as Brown Public. Public saw this as an opportunity to show viewers what often remains unseen.

“They asked me to try to capture the atmosphere of homelessness or being unhoused. I tried to take some pictures that kind of highlighted some of the problems and the pains of what unhoused people go through.” Public said.

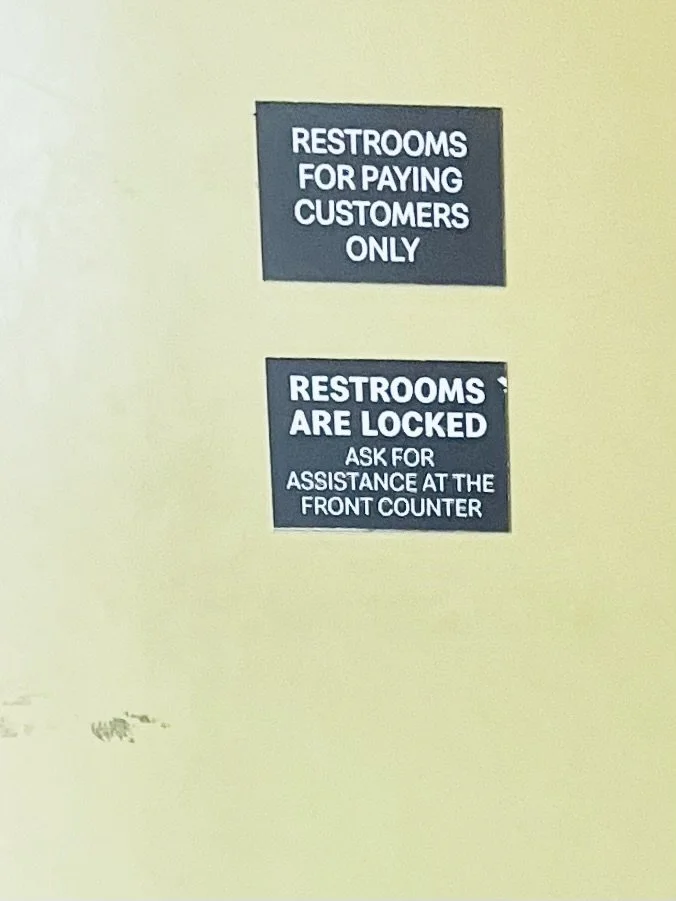

One of Public’s images, titled “Locked Out,” shows a sign on a bathroom door that says, “Restrooms are for paying customers only.”

Restroom access is a recurring theme throughout the exhibit.

“Originally, I was trying to show just all of the hang-ups that come with having to go to public restrooms or trying to make money, and have people steal your things. Trying to show how life is for the unhoused people. Just things on average that the average homeless person or unhoused person has to deal with that others may take for granted,” he said.

Public said signs that prevent the unhoused community from accessing a restroom or other facilities demonstrate how little value and respect are given to them. Flood said she was struck by the resilience and beauty revealed in the images.

“What hit me was honestly the beauty that people are still able to see in the world,” she said. “They are pushed down, marginalized, stomped on by the systems. And yet, so many of these pictures people took were of really beautiful things that make them feel safe, happy, and hopeful.”

THE IMPORTANCE OF ANONYMITY

According to Flood, participants were given the option to use pseudonyms, and everyone chose to remain anonymous. Anonymity was important for many of the artists because they didn’t want to be defined by their experiences living on the street.

“When we’re housed, we get to tell our stories about parts of our life and our experience in the way that we want. We really wanted the artists to be able to express however they were feeling, whatever they were thinking in the way that they wanted without having to think about how their participation may follow or define them down the road,” Flood said.

Flood said she felt that anonymity allowed individuals to share their stories without having labels and narratives unfairly forced upon them.

“We wanted them to be free to share however they were feeling and for that to be it, for it not to be associated with how anyone else knew them or had an experience with them. We wanted it to just truly be the perspective and story they wanted to share,” she said.

BUILDING EMPATHY

Mirrors placed throughout the gallery invite visitors to consider prompts such as What resonates with you? and What did you learn here?

“The hope, my hope, is for people who attend the exhibit to really take in the visual story and the written story that accompanies it in the narrative, and to be able to step into a moment where they truly see through the eyes or lens of the artist,” Flood said.

For Public, the exhibit was about reaching people who may not understand the challenges of being unhoused.

“My hope was to just draw them in, even if a little bit closer, to something that may not be their reality. And that’s the gist of basically what I was trying to do with my photography and all of my art,” he said.

Flood said the project underscores the need for more spaces where people can share their own stories.

“The only hope we have of solving our most pressing challenges is to really heal the separateness that is pervasive in society right now. And my belief is the pathway to that is through stories,” she said.