Hickenlooper on Homelessness

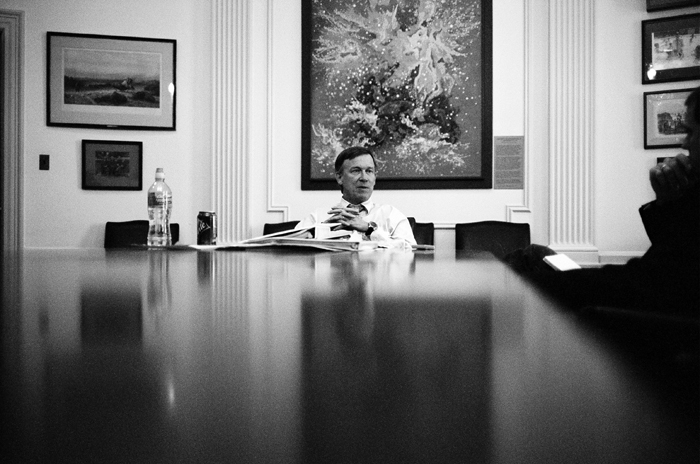

Mayor John Hickenlooper discusses Denver's 10-year plan

Mayor John Hickenlooper discusses Denver's 10-year plan

By Tim Covi

Photography by Ross Evertson

From an English major in undergrad, to a master’s student in Geology, from a young entrepreneur in a derelict part of 1980’s Denver, to the Mayor’s office, John Hickenlooper’s path to politics has been anything but direct. In office, he has led this city through huge changes and growth. He’s pushed for greater accountability in sustainable development, in green house gas emissions, and in police department reforms.

As he embarks on the Governor’s race, we sat down with him to discuss one of the defining aspects of his tenure in the Mayor’s office, Denver’s Road Home, our 10-year plan to end homelessness.

Five years into this plan, Denver’s Road Home has accomplished several of its numeric goals in terms of providing services, though the homeless population has grown. Though well short of ending homelessness among either chronic or temporary populations, DRH has managed to bring more than 1,500 housing units online for the homeless, and has made homelessness a central aspect of community action in Denver.

The recession triggered a spike in Denver’s homeless population, which grew from 2,628 in 2005 to 6,659 in 2009, or almost a 61 percent increase. Much more needs to be done to solve the problem. Without the centralized services created by DRH, the coordination of faith based efforts to support the homeless and the infusion of money generated by DRH, this population will balloon more.

Mr. Hickenlooper talks to us about how DRH started, what motivated him to throw his weight behind it, where we need to go from here, and how successful aspects of DRH could be applied across the state.

We’re about mid-way through Denver’s 10-year plan to end homelessness. So in the past 5 years, what do you think has made aspects of it so successful?

You know to a large extent, the success of Denver’s Road Home is not the result of the Mayor’s office, but the result of a process that brought together the community. I mean all the affected parties, right? Not just homeless [service] providers, but businesses on the 16th Street Mall, hotels, sports-teams. You know, any business that had a brand, that their identity, their brand is somewhat dependent upon how Denver is seen, we went out to and said, “We want you to help on this.” And [in] that original 18-month process…more than 300 people came to at least two successive meetings. That level of participation really created…a matrix by which we could address the problem. And we’re not gonna see how many meals can you provide to the homeless; we’re gonna see how many fewer meals can you provide because we’re going to have less homeless. And at least to my knowledge it’s the first time, certainly in the history that anyone’s aware of in the city, but really one of the first times in the country, where all the measurements were about ending the problem. Not providing a service, but ending a problem.

Go back to the beginning of Denver’s Road Home. Why was this something that you felt so strongly about? Your background was in business and isn’t necessarily characterized by social issues. So what made this something that you wanted to take on?

Well I thought it was a symbol of the fundamental nonsense of government, that we would spend so much money addressing homelessness without success. Or with such limited success—obviously we had some success, we kept people from dying, you know. But in terms of really addressing the issue itself, we had such little success. When I was building the Wynkoop brewery company—I mean we were so underfunded that we had to do all the paint scraping ourselves and all the floor sanding ourselves, all that work, built the booths and the bars and the benches. And there were a couple of homeless guys that lived in our alley; we would hire them for weeks at a time, they would fall off the wagon and we’d lose them; we wouldn’t see them for a couple weeks and then they’d come back and we’d hire ‘em again. You know, just the grunt work. We paid them I like $5 bucks an hour, $6 bucks an hour [mid to late 1980’s]. And, you know we never had time to follow and pursue them and figure out where they went and why they fell off the wagon, what happened. I mean, we got to know them pretty well, but we were just too busy. And it always kind of bothered me that we were too busy, everybody was too busy. And these were pretty good guys. I mean, when they were working they were good workers, they were good people, everyone got along with them. And then once we opened the restaurant there was another guy who lived down at the far end of our alley that I saw almost everyday for like 3 or 4 or 5 years when we first opened. He finally moved to Arizona, I heard through the grapevine. And that rang in my mind; that for so long he was just living there. … [Another] part of it was when we hired Roxanne White as the head of human services. You know she was one of my very first appointments. …and she felt exactly the same way I did. In that first interview…the one thing we kind of hit on that we both really cared about were [the] homeless.

You’ve talked a little bit about your business background and you’ve obviously got an eye for social issues. These two things, how do they go together in a 10-year plan?

Well it’s a business approach to a social issue. Denver’s Road Home is really like a business plan to address homelessness. You measure the problem. How many homeless are there? How much money are we spending on them? Of all those different streams of funding, which ones are really getting results? What would be a better way to do it? What are the crucial, the critical issues in getting someone out of homelessness? Not just getting them into shelter, but what is the real [issue]. And very early on we saw that the real issue is a job. I think that’s where a lot of disconnects have happened before. … Sure we want to get someone into housing. We want them off the street, make sure they’ve got medication, and counseling if they’ve got addictions, medications if they’re mentally ill. But most importantly we wanted to get them a job. You know that was just a lightning rod —that we wanted to help these people help themselves. And some of these [businesses], like Snooze, you know the coffee shop Snooze, had hired a number of chronically homeless individuals and stuck by them. Guys would fall off the wagon, not show up for work for a day or two. But they’d take them back. John would say, “Alright we’ll give you another chance.” Ultimately several of them became model employees. I think that was where the rubber really met the road [when] we said “Alright, we’re gonna have a business plan, were gonna measure, we’re gonna make a model … and then we held ourselves accountable.”

Well it’s a business approach to a social issue. Denver’s Road Home is really like a business plan to address homelessness. You measure the problem. How many homeless are there? How much money are we spending on them? Of all those different streams of funding, which ones are really getting results? What would be a better way to do it? What are the crucial, the critical issues in getting someone out of homelessness? Not just getting them into shelter, but what is the real [issue]. And very early on we saw that the real issue is a job. I think that’s where a lot of disconnects have happened before. … Sure we want to get someone into housing. We want them off the street, make sure they’ve got medication, and counseling if they’ve got addictions, medications if they’re mentally ill. But most importantly we wanted to get them a job. You know that was just a lightning rod —that we wanted to help these people help themselves. And some of these [businesses], like Snooze, you know the coffee shop Snooze, had hired a number of chronically homeless individuals and stuck by them. Guys would fall off the wagon, not show up for work for a day or two. But they’d take them back. John would say, “Alright we’ll give you another chance.” Ultimately several of them became model employees. I think that was where the rubber really met the road [when] we said “Alright, we’re gonna have a business plan, were gonna measure, we’re gonna make a model … and then we held ourselves accountable.”

And have Denver businesses embraced this well enough in your opinion?

Well there’s always more that needs to happen. I mean…Lincoln said: “With public sentiment nothing can fail, without it nothing can succeed, that is why those who mold public sentiment go deeper than those who enact statutes or pronounce decisions.” And we focused right from the beginning on public sentiment. So how do we get these businesses together and show them, this is a business model. We’re not asking you to donate money that you’re throwing away, you know, just perpetuating a lack of misery. We’re gonna try to change a social condition, and there was a real appetite for that.

I think, realistically, jobs are the most critical element that we can provide to people, homeless or not.

Agreed. Yep, quality of life starts with a good job.

And I think this is probably one of the hardest questions to answer as a politician, but how do we actually bring jobs to Denver, to Colorado, that are valuable to this population of people? Because we need to face it. The majority of people who are homeless aren’t really former lawyers or bankers. There might be some, but they’re not the majority. They’re working class folks.

I think [it’s] all the service level jobs, right? So you know you go work…as a bar tender or a waitress and you’ll make $12-$15 bucks an hour. One of the biggest challenges now is how do we get more livable wages for people that are doing those kind of jobs. You know, the butcher at Safeway probably makes $17 bucks an hour, $18 bucks an hour with pretty good benefits. The butcher at Wal-Mart, I don’t know what they make, you tell me—$11 bucks, $12 bucks an hour, minimum benefits? … There are plenty of jobs; our problem is that we’re not paying enough to them, right? And if anything homeless individuals…often times they can get a section 8 voucher or some sort of subsidy so even if they’re making $8 bucks an hour, they can at least come pretty close to getting by. But that’s hard. That’s a hard life.

I think that a lot of people have fears and then also some pretty big misconceptions related to hiring homeless people. Very candidly, how would you approach business owners and make people feel more comfortable with employing people who are homeless?

Well the amazing thing, this is like when we opened Wynkoop. This is another one of the things that made me address homelessness. There were a lot of chronically homeless people around LoDo back in those days. The mid-80’s. But if you looked at the crime rates, the crime rate was incredibly low. So I had this huge perception issue when I was trying to get investors to invest in a brewpub, you know, opposite Union Station. People kept saying, “Oh is it safe? Is it safe!?” And I showed them the police reports and they were incredulous. It was one of the safest parts of the city. Because basically, homeless individuals, the vast majority are non-violent. They’re perfectly safe. They may get into fights with each other once in a while, but pretty rarely. Your biggest challenge with hiring a homeless person is them giving into their addictions and falling off the wagon in one-way or another. But there’s very little, or much less chance that they’re going to harm someone, or steal, or do some sort of really destructive behavior. So I think that’s one of the things that we pitched to the business owners—is that this is a relatively low risk way to do something very positive for your community.

Well the amazing thing, this is like when we opened Wynkoop. This is another one of the things that made me address homelessness. There were a lot of chronically homeless people around LoDo back in those days. The mid-80’s. But if you looked at the crime rates, the crime rate was incredibly low. So I had this huge perception issue when I was trying to get investors to invest in a brewpub, you know, opposite Union Station. People kept saying, “Oh is it safe? Is it safe!?” And I showed them the police reports and they were incredulous. It was one of the safest parts of the city. Because basically, homeless individuals, the vast majority are non-violent. They’re perfectly safe. They may get into fights with each other once in a while, but pretty rarely. Your biggest challenge with hiring a homeless person is them giving into their addictions and falling off the wagon in one-way or another. But there’s very little, or much less chance that they’re going to harm someone, or steal, or do some sort of really destructive behavior. So I think that’s one of the things that we pitched to the business owners—is that this is a relatively low risk way to do something very positive for your community.

This brings me to another thought with 10-year plans. There are probably more than 300 of these across the country now. I think that’s great. And then there’s the other side of it which is: how do you get this to go from being a plan, and just lip service and people talking, to actual movement? Because Denver has obviously had a lot of success, but a lot of other communities haven’t been able to get the money or the drive behind it.

Well in Fort Collins I went up and spoke to them a couple weeks ago. I think it’s gonna happen. And I think, in the end, it doesn’t take all that much money. It took a bunch of money in Denver because we had a huge homeless population compared to Fort Collins or anywhere else. ... Part of what it was for us, was figuring out—where are all the different funds that we’ve never tapped, right? And those funds are available to everybody. They’re available to Colorado Springs and Grand Junction. I mean, look at the money we have available through Veterans Affairs.

What was that like?

Oh… in my opinion the Veterans Administration was spending a lot of money to provide services for veterans that were perhaps not the most in-need veterans, not the people who had the most critical challenges. When I first went to Washington and told [Jim Nickelson] I’d love to get some veterans money, some VA money, but [for] prevention, not while they’re in the hospital, but prevention, and really have it for housing and medications and job training. God they were supportive.

Some states have passed 10-year plans, and have adopted it as a statewide policy. Do you think this is something that you’ll take to a state level if you get elected?

Well we’ll have to see what the landscape looks like, but I think that it is a problem that lends itself to a statewide solution. You know, the whole “one home, one congregation”…notion is that…we have roughly 1,100 congregations in metro Denver; we had roughly 1,400 homeless families. So the notion is you get one congregation to take responsibility for a family. And what— we’re over 1,500 homeless individuals that have been helped with this thing? For a fraction of the cost of other government services? A fraction! You know that kind of stuff works just as well on a statewide level as it does on a city level. •