Local Buzz: Schooling Shelters

Published January 2010 Vol. 14 Issue 1

text by Michael Neary

photography by Adrian DiUbaldo

Living at the Salvation Army Lambuth Center in Denver, Luz Hernandez and her two children face some uncertainty about their future. But uncertainty and all, their lives clearly feel better to them than they did last spring.

About six months ago, Hernandez was holding down two jobs while the family lived in a Westminster apartment. The jobs—part of an effort to emerge from a deepening financial trench—left little time for Hernandez to spend with her daughter Lesley Velasquez, 13, and her son Adrian Velasquez, 12.

“I would hardly see them,” she said.

Hernandez, who spoke quietly, seemed to relish the time she could now spend with her children.

Hernandez talked about her move to the shelter as her son worked on lessons in a tutoring program begun this year by Denver Public Schools. Luz said her daughter, who wasn’t at the shelter that afternoon, would also be taking up the lessons. With wooden floors and modest but comfortable chairs, the shelter is an inviting place, and the moods of the families staying there seemed serene.

The children at the shelter are studying in ways they wouldn’t have been able to a year ago. DPS started the tutoring program where Adrian was learning with federal funds made available by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The ARRA funds are part of a big increase in federal dollars available to Colorado public schools to help homeless students this year—but the problem itself is growing at a daunting pace.

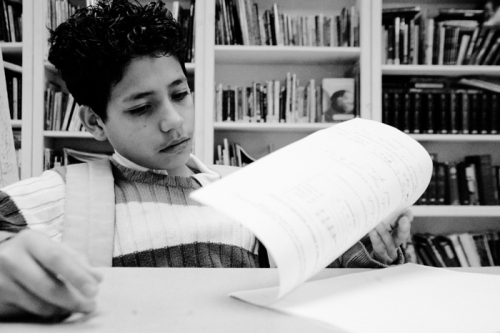

Adrian Velasquez, 12, works on a math worksheet at the Lambuth Center.

Colorado’s homeless student population crept up to 12,302 in the 2007-08 school, compared with 11,978 the year before, according to data submitted by the state to U.S. Department of Education. But by the end of last spring, that number had grown by a leap. Colorado’s 2008-09 end-of-school-year report to the USDE tracked 15,834 homeless students, according to Dana Scott, the Colorado state coordinator for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth. That’s a 24 percent increase over the previous school year.

It’s a trend that extends throughout the nation, with unemployment and foreclosures driving much of the increase. John McLaughlin, federal coordinator of the Education for Homeless Children and Youth Programs with the U.S. Department of Education, noted a decrease in the population of homeless students the year after a spike produced by Hurricane Katrina, in 2005. But it didn’t last long.

“After a steep increase due to Katrina in the 2005-06 school year, there was a decrease in reported student enrollment the following year, but the numbers are trending back up to that peak,” he wrote in an e-mail.

Barbara Duffield, the policy director of the National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth, estimates a public school enrollment last year of more than a million homeless children from preschool through high school, based on reports from states and school districts. NAEHCY is a non-profit organization that, according to Duffield, provides technical assistance for homeless students and acts as a policy advocate for the students.

These swelling numbers have created a knot of intertwining of social problems, according to Scott.

“Not only are numbers escalating,” she said, but so is the “complexity of kids’ cases.”

Scott noted growing combinations of unemployment and domestic violence, and she explained how even the most well-intentioned families—with the help of a bad economy—may be short-circuiting their children’s education. She described a Colorado woman who needed to hold onto a job in order to keep the transitional housing where she and her children lived. Unable to find affordable childcare, she arranged for an older child to stay home from school to mind a younger child.

In that case, Scott said, the school district was able to “get resources to keep that (younger) child in all day kindergarten,” freeing the older one to return to school. But Scott said the scenario is a common one—an observation echoed by others working in the field.

“That’s a huge issue,” said Sarah Pierce, a children’s advocate for The Gathering Place, a Denver day shelter. “We’re seeing that constantly.” A parent might, she explained, say that “I kept them home because they help out with the siblings.”

That’s a practice, Pierce said, that The Gathering Place does not allow once staff members see it happening.

What the numbers and even the anecdotes do not always reveal, though, are the cases of homelessness—or pre-homelessness—that occur in the hidden regions away from shelters. Scott explained that the federal definition for homeless students includes living in shelters, cars and streets—along with a more inconspicuous style of homelessness.

“A big one for education that looks a little different from other agencies is [that] we include people who are doubled up due to economic stress,” she said.

And it may be in those cases, far from the reach of social services, that students endure some of the toughest strains. They also may not always exhibit clear signs of duress in the classroom—at least in terms of academic performance. A Mapleton High School student who asked to be called “Dave” said he lived in the garage of his relatives between August 2008 and April 2009. He now stays at the Urban Peak shelter in Denver.

Bridget Watkins tutors the Velasquez’s and other homeless children at the Lambuth Center.

Bridget Watkins tutors the Velasquez’s and other homeless children at the Lambuth Center.

Dave said he did well in his classes during the rough time he was relegated to the garage, where he said he had to sleep in cold weather right through the winter months. He described the school as a “resting place” where he could study, bathe and eat in relative peace.

“That’s the only place I ate, at least during the day,” he said.

For Hernandez and her family, the toughest times also seemed to occur outside of the shelter where they now stay. Hernandez’s son Adrian described sometimes waking up at 3 a.m. in the family’s old Westminster apartment and hearing his mom preparing to go to one of her jobs. That, said Adrian, could take a toll the next day at school.

“It’s hard to wake up in the morning,” said Adrian, a sixth grader who now attends Valdez Elementary School, as he recalled those days in the apartment. Hernandez said her mother would mind the children when her work schedule ate up large bites of time.

The funding to help students in Adrian’s position has grown—at least for now. Scott said Colorado’s regular federal allocation for the 2009-10 school year under the McKinney-Vento Act is $830,000, a total that’s up from last year’s $500,000. The state is also receiving $488,548 this year to be used to help homeless students under ARRA.

“We’ve been able to get into areas of the state where we’ve never been before,” said Scott, noting programs in the San Luis Valley, as well as other parts of the state. She said programs for homeless students have now entered 48 of the state’s 178 school districts, compared with programs in 32 districts a year ago. But she said the increase ranged beyond those numbers. She noted that many of the districts that already had been receiving help began receiving much more intensive help with the new funding.

Still, Scott said, the funding is limited considering the expenses that school districts can incur from assisting homeless students. One of those expenses flows from transportation. Scott said the financial burden can discourage school districts from identifying homeless students.

“We’re seeing this tension with districts around identification, because the more you identify, the more you have to serve, the more fiscal impact there is to the district,” said Scott.

Anna Stout, a homeless liaison in the Educational Outreach Program of DPS, said the district typically spends between $80,000 and $90,000 on transportation for homeless students each year.

But as dire as the financial situation of school districts may be, this year’s deeper reservoir of federal money to help homeless students has sparked the creation of new services.

One effort launched with ARRA funds is the tutoring program for homeless students at DPS—the program where Adrian was studying. Stout said the program focuses on the northwest part of the school district, an area she said experienced a 22 percent increase in homeless students last year.

Stout said rising rents, foreclosures and job loss all combined to heighten the problem of homelessness in the area. So, district officials drew from the $35,000 allotted to DPS homeless programs through ARRA to begin a tutoring program. They hired Bridget Watkins, who’d been working as a substitute teacher, to coordinate it and to conduct the sessions.

Stout said the sessions do not follow a set curriculum, but instead are designed to help students dig into the lessons they receive at their schools. She said the district sent surveys to several northwest Denver public schools, along with a few shelters, and discovered the most requested service to be tutoring. The need, Stout said, was for a “quiet place for our kids” to focus on school in what can be less-than-quiet living conditions.

Duffield, with NAEHCY, said many tutoring programs for homeless students exist throughout the country, but she said she was not aware of any “systematic study” to gauge their effectiveness.

Watkins works both in schools and in shelters where families stay. She said math and writing tend to be particular areas of focus during the sessions, but she also described the tutorials as safe places where children can work on projects separate from whatever struggles have left them homeless.

“When they come through that door they know it’s about homework and they know that this is what they’re going to work on,” Watkins said. “They don’t come in saying, ‘I’m not happy because we’re still here,’ or ‘My mom’s going through this (struggle)’ … When they come through that door it’s a whole new situation and they can sort of leave that behind.”

On a recent afternoon at a tutoring session at the Salvation Army Lambuth Center shelter—one of Watkins’ tutorial sites—students appeared to be doing just that. About a dozen students worked congenially and sometimes playfully in what at times looked like an ordinary school classroom, except that the students ranged in age from preschool to high school. During the session, Watkins circulated from table to table, delving into flashcards, books and worksheets.

She also had help from Kalisha Frazier, a young woman who worked mostly with her two daughters—Journey, who’s 3, and Faith, who’s 2—but who freely helped out other children as well.

Frazier, like others at the shelter, illustrates the ripples of complexity running through the lives of parents who, with their children, suddenly find themselves in crisis. Frazier said she loves school, and when she reads to her children she’s visibly conveying that love. She’s a hair’s breadth—or a semester—away from a bachelor’s degree in social work; she’s also a few months removed, she said, from a living situation that involved domestic violence.

Frazier said the new living arrangements are unusual for her and her family since they’re used to their independence. She recalled how she used to shield her children from certain behaviors that now, with so many children around, they’re bound to see.

So nowadays certain actions, no longer out of sight, can serve as “teaching tools,” she said, or “behavior I can talk to them about.”

Frazier’s is another family that may be enduring challenges right now, but that also emerged from predicaments that were much worse—and, according to those close to the scene, that are increasingly common. With some outside help and through their own creativity, Frazier and Hernandez now appear to be helping their children to thrive at school in ways that were impossible for them just a few months ago.

“They’ve been my passion for the last three years and I want them to be able to succeed in school,” Frazier said. “I enjoy school and I want them to enjoy learning.”

The next step for these families is less than certain, but the children poring diligently over everything from coloring books to geometry books in Room 204 of the Salvation Army Lambuth Center seem oblivious—at least for now—to that uncertainty.

“We’re seeing this tension with districts around identification, because the more you identify, the more you have to serve, the more fiscal impact there is to the district.”

—Dana Scott